Is quartzite very porous? Why is there such a wide range in feedback from others experiences? Well, simply and truthfully, not all material labeled as quartzite is a true quartzite… and this a cause of great confusion.

The reason for mislabeling stone can be varied: inadvertent over-generalization or classification of products, misinformed industry professionals, or the fact that some material types can often draw a higher premium than others and, therefore, an attempt may be made to pass of one material for something it is not.

We will quickly dive into this, clear up some confusion, and help you understand your material better. With varying levels to the life-cycle, some natural stone is lumped into the quartzite category when, in fact, it is lacking in some key developments. While there is no distinct point at which a rock officially transforms from sandstone to quartzite, we can look at certain criteria which may aid us in best classifying a particular color in question with its closest stage. This, in return, will help us set better expectations on how our countertops will perform.

Sandstone

Let’s start with sandstone. Quartz-based sandstone is a sedimentary rock formed from large deposits of sand-sized grains of weathered rock, which are compressed and then fused together with silica based (or sometimes calcite based) cement agents. These binding agents have been carried down between the individual particles of sand by ground water- which may introduce other impurities that can, incidentally, add to the stone’s unique color. At this stage in the life of the stone, sandstone can already be quarried into beautiful slabs suitable for countertops. The material can and will be very scratch resistant (about a 7 on the Mohs scale) due to the grains of quartz- which can make it seem like regular quartzite; however, the looser mineral structure of the bonding cement in between will leave it relatively porous (unlike true quartzite). You will often see very distinct banding (or stripes) in the movement of the stone in this class. These bands were influenced by strong river currents, or winds, which formed striations or mountain range-like patterns across the sandy surface- prior to the extreme pressure which formed the material into a stone. Upon closer inspection with a magnifying glass, or sometimes noticeable to the naked eye, stone in this relatively younger stage will still exhibit composition of individual grains of sand. Again, liquids will pass, with some degree of ease, between these grains of sand- through the cementitious binders. Even with regular sealing, this stone will likely be prone to staining. A few common colors of sandstone, which are often mislabeled as quartzite, are Wild Sea, White Sea, and Lavender Grey.

Intermediate Quartzite

If, on the other hand, this material were to undergo an additional amount of heat, pressure, and chemical activity, the sandstone may be heated and fused back again into a more solid structure- this is a transformation from a sedimentary to a metamorphic rock. In this case, the individual particles of sand and binding agents lose some of their unique structure and the entire formation begins to take on more of an interwoven structure. Banding is still often noticeable at this stage. However, it may be more difficult to detect the individual grains of sand in its make-up. Stone, in this stage, should preform well with a regular sealing regiment. Examples of common “Intermediate” quartzite are Mont Blanc, White Macaubus, and Infinity White. The advancement in fusing particles together makes the intermediate level less porous than sandstone.

Crystalline Quartzite

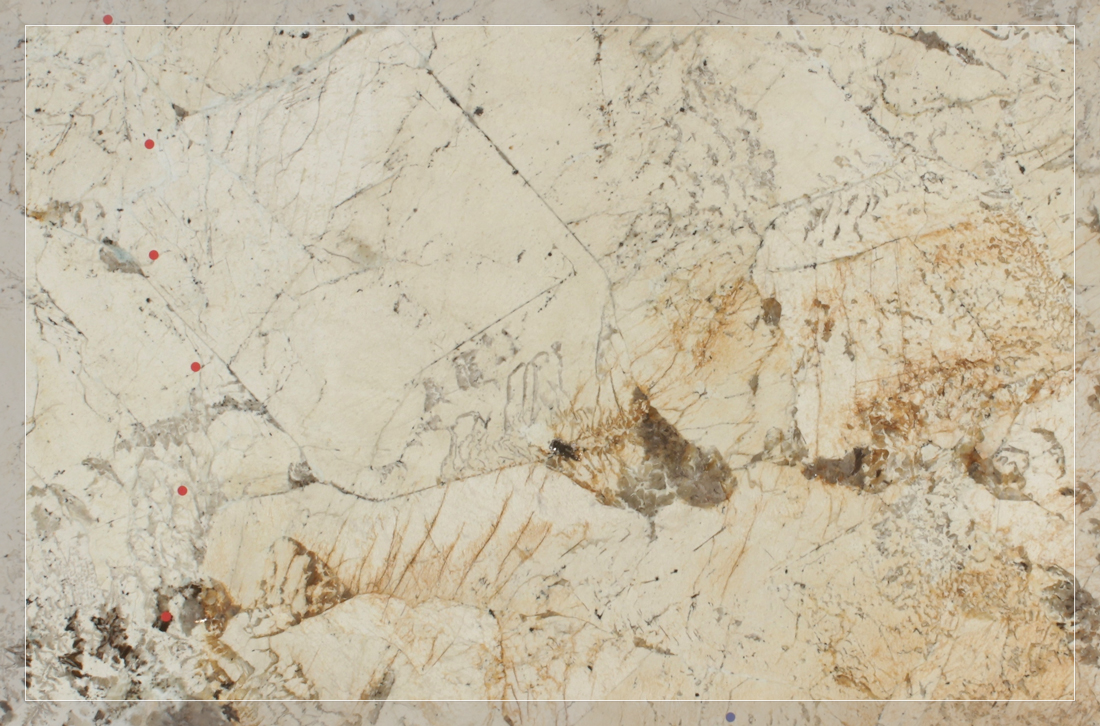

Similar to layers of snow being compressed under such immense pressure that each flake loses its individual structure and is, instead, fused into a solid glacial ice formation… so shares the seamless structure of crystalline quartzite. Crystalline quartzite, like sandstone and intermediate quartzite, boasts extreme durability for scratch resistance… yet also adds an element of increased density making it far less porous than the preceding formations. True quartzites will have limited-to-no distinct vein formations, no visible grains in the composition, and this tightly interlocking structure will boast a very low absorption rate. White and gray are common colors for true quartzite, but you may find other colors due to inherent impurities like the warm tans, reds, and bronzes of a rusty iron oxide. Taj Mahal and Sea Pearl are common crystalline quartzites.

Summary

There are hundreds of colors of stone readily available in most local markets, a consistently updating list, and there are more classifications to stone than discussed in this document. E.g. there exists types of stone which can blend marble and quartzite together in the same slab. So, the information contained herein is not intended to be all inclusive. Rather, these explanations are intended to help clarify the confusion as to why some “quartzite” appears to be more problematic than others, in regards to staining. It is always recommended to perform tests on your material before making a final purchase. Samples can be provided to the customer to be sealed and tested for suitability for service. If you have any additional questions or concerns, please contact your Project Manager at BBG.